29 Mar Beyond the body, perfection is feminine

by Serena Nardoni

ENG

Breezy is curating an exhibition that will be held in Rome, at the Ex Cartiera on the prestigious Via Appia Antica, on April 22nd – 30th, to investigate the complex relationship between human beings and technology through the eyes of our time. To introduce the event and all the artists who will take part in it, we would share with you the process of research and study behind the creation of a curatorial concept titled: I(m)perfection: the laws of technology that dominate order and chaos. We will do this with short essays that will look at technology in its relationship with the concept of beauty, in its evolution through the centuries. We will talk about art and philosophy, order and chaos, mathematical weighting and improvisation. The question with which we want to introduce you to the reading is: Where does the purest and most authentic concept of beauty reside? In the proportion and balance of forms or, rather, in the undisciplined chaos?

ITA

Breezy sta curando una mostra che si terrà a Roma, presso l’ex Cartiera sulla prestigiosa Via Appia Antica, il 22 – 30 aprile, per indagare il complesso rapporto tra essere umano e tecnologia con gli occhi del nostro tempo. Per accompagnare l’evento ed introdurre tutti gli artisti che vi prenderanno parte, abbiamo pensato di condividere con voi il processo di ricerca e studio che c’è dietro l’ideazione di un concept curatoriale dal titolo: I(m)perfection:le leggi della tecnica che dominano l’ordine e il caos. Lo faremo con dei brevi saggi che guarderanno alla tecnologia nel suo rapporto con il concetto di bellezza, nella sua evoluzione attraverso i secoli. Parleremo di arte e filosofia, di ordine e caos, di ponderazione matematica ed improvvisazione. L’interrogativo con cui vogliamo introdurvi alla lettura è: Dove risiede il concetto più puro e autentico di bellezza? Nella proporzione ed equilibrio delle forme o, piuttosto, nel caos indisciplinato?

Beyond the body, perfection is feminine

ENG

Over the centuries, the image of the female body has always been a vehicle for the transmission not only of a canon of aesthetic beauty, but also of social and political ideals.

An evolutionary theory based not so much on adaptation to living conditions in the strict sense of the word, but rather on the need to place women within this “role game” that is social living. We could talk for pages and pages about what it meant (and still means) to be a woman, but it is art that has taught us the communicative power of images. It is through art that we can glimpse sensuality, submissiveness, power, devotion to work and family, sadness and pride. Here the figure of the woman becomes a mirror of the society in which she lives, a balance of contrasting forces and emotions, a measure of the civilization of a people and the personification of the models chosen for her by the male power.

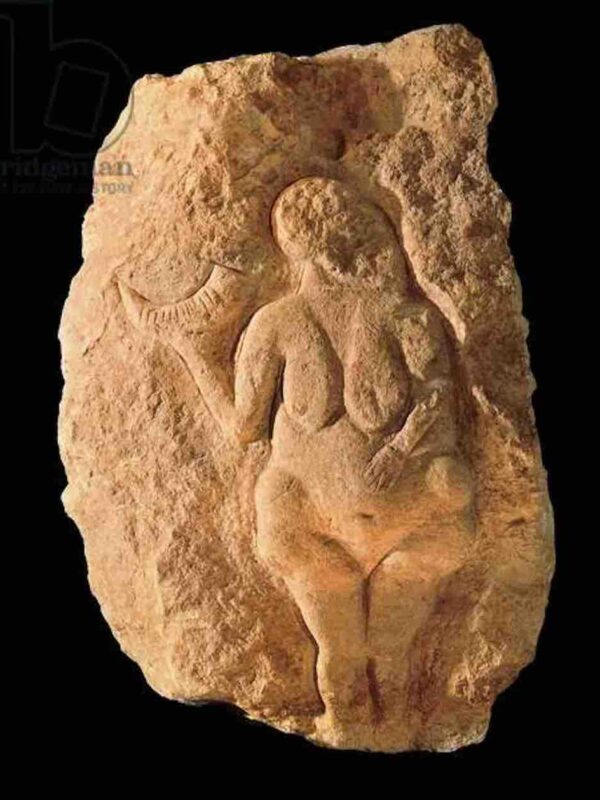

Why invest the woman with such a responsibility? The answer is quite simple and has its roots at the dawn of our history: the famous Venus of Laussel belongs to the Upper Paleolithic, representation of a shapely and generous female body, symbol of fertility. Fertility is life, is the continuation of the species and salvation.

Oltre il corpo, la perfezione è donna

ITA

L’immagine del corpo femminile è sempre stata, nei secoli, veicolo di trasmissione non solo di un canone di bellezza estetico, ma anche di ideali sociali e politici.

Una teoria evoluzionistica fondata non tanto sull’adattamento alle condizioni di vita in senso stretto, quanto piuttosto sulla necessità di collocare la donna all’interno di questo “gioco di ruolo” che è il vivere sociale. Potremmo parlare per pagine e pagine di cosa sia significato (e significhi tutt’ora) essere una donna, tuttavia è proprio l’arte che ci ha insegnato il potere comunicativo delle immagini. Proprio attraverso l’arte possiamo scorgere la sensualità, la remissività, il potere, la devozione al lavoro e alla famiglia, la tristezza e la fierezza. Ecco che la figura della donna diviene specchio della società in cui vive, bilanciamento di forze ed emozioni contrastanti, metro di misura della civiltà d’un popolo e personificazione dei modelli scelti per lei dal potere maschile.

Perché investire la donna di una tale responsabilità? La risposta è piuttosto semplice e affonda le proprie radici agli albori della nostra storia: appartiene al Paleolitico superiore la famosa Venere di Laussel, rappresentazione di un corpo femminile formoso e generoso, simbolo di fecondità. Fecondità è vita, è prosieguo della specie e salvezza.

ENG

An evidently utilitarian function of the woman, without too much mystery or expectation. Components which enter with force in the representations of women in the Egyptian age. The ideal of female beauty in vogue in Ancient Egypt, in fact, corresponded to a slender body, with a high waist and narrow shoulders, with a symmetrical face, with an inscrutable and shy look, that communicated elegance and enigma, grace and strength.

But it is with the Greek civilization that we begin to address the role of women in society. Despite the awareness that she was a figure subordinate to man, defender of the homeland, rock of the family, holder of political power and knowledge, in Greece there were examples of reversal of these beliefs. The Amazons are a striking example, as mortal women represented as warriors fighting against the Greeks. The war is what makes them women, strong and unique in their coven, becoming bearers of an iconography all their own that sees them represented without the right breast, burned at an early age to have much more strength in the arm that stretched the bow and held the weapon.

A destiny, that of the woman-warrior, brought to its maximum expression in the representation of Athena, one of the major divinities of the Greek Pantheon. Yet, in order to find herself with her “colleagues”, Athena was born from Zeus, a male divinity, and was forced to renounce her own femininity, remaining a virgin.

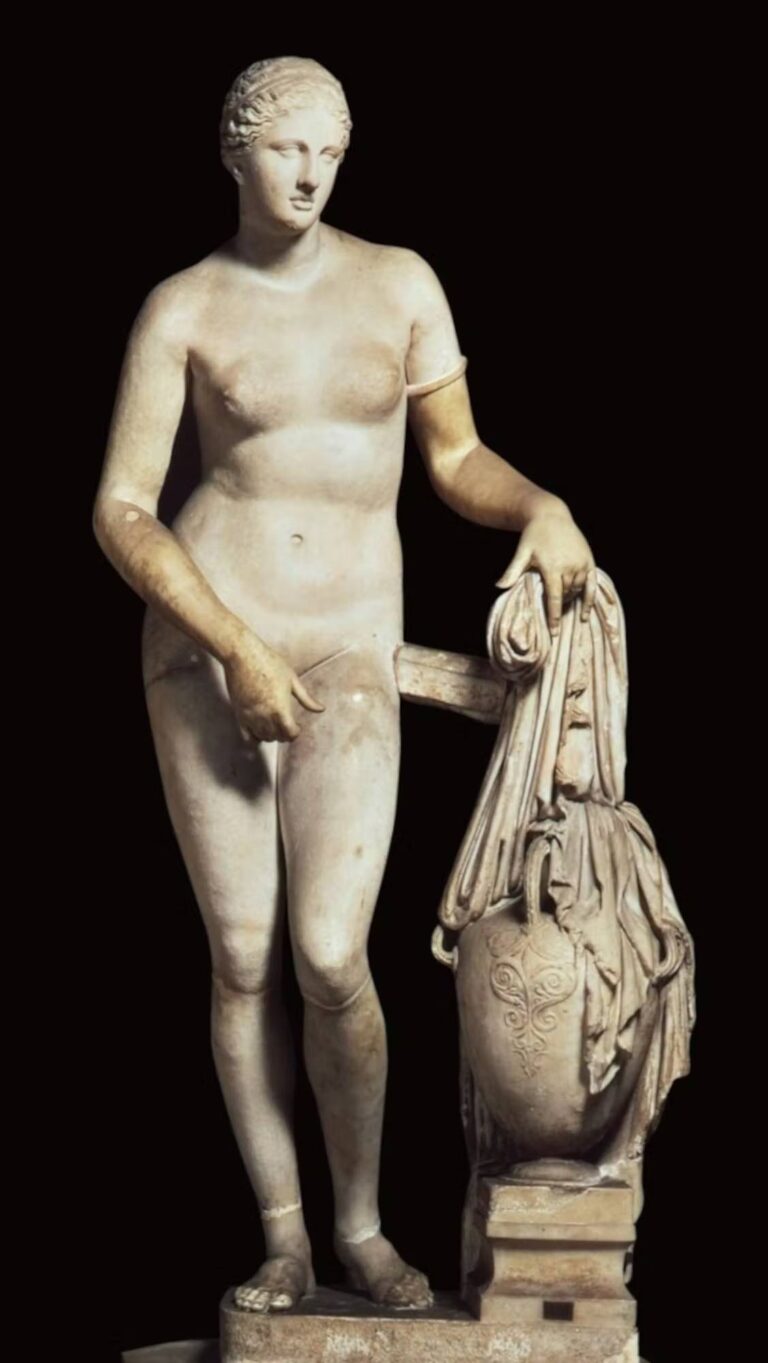

The Amazons and the representation of Athena cannot therefore be said to be ideal models to aspire to, for a Greek girl… Rather, graceful, sweet and sinuous figures such as the korai of the archaic age better lend themselves to examples of virtue. But among these sweet and subdued maidens, one stands out in history for its impudence and beauty: it is the Aphrodite of Cnidus, a work created by the sculptor Praxiteles around 330 BC and passed into history for being the first life-size female nude statue (the original has been lost, but hundreds of marble versions have been made).

ITA

Una funzione evidentemente utilitaristica della donna, senza troppo mistero o aspettativa. Componenti, queste ultime, che entrano con forza nelle raffigurazioni di donna in età egiziana. L’ideale di bellezza femminile in voga nell’Antico Egitto, infatti, corrispondeva ad un corpo esile, dalla vita alta e le spalle strette, con un volto simmetrico, dallo sguardo imperscrutabile e schivo, che comunicasse eleganza ed enigma, grazia e forza.

Ma è con la civiltà greca che si inizia ad affrontare il ruolo della donna nella società. Pur nella consapevolezza che fosse una figura subalterna all’uomo, difensore della patria, roccia della famiglia, detentore del potere politico e del sapere, in Grecia non mancarono esempi di rovesciamento di queste convinzioni. Le amazzoni ne sono un esempio lampante, in quanto donne mortali rappresentate come guerriere in lotta contro i Greci. La guerra è ciò che le rende donne, forti e uniche nella loro congrega, divenendo portatrici di una iconografia tutta loro che le vede rappresentate senza il seno destro, bruciato in giovane età per avere molta più forza nel braccio che tendeva l’arco ed impugnava l’arma.

Un destino, quello della donna-guerriera, portato alla sua massima espressione nella raffigurazione di Atena, una delle maggiori divinità del Pantheon greco. Eppure, per trovarsi con i suoi “colleghi”, Atena nasce da Zeus, divinità di sesso maschile, ed è costretta a rinunciare alla propria femminilità, rimanendo vergine.

Le amazzoni e la raffigurazione di Atena non possono quindi dirsi modelli ideali cui aspirare, per una ragazza greca… Piuttosto figure aggraziate, dolci e sinuose come le korai di età arcaica meglio si prestano ad esempi di virtù. Ma tra queste dolci e sommesse fanciulle una spicca nella storia per impudicizia e bellezza: è la Afrodite di Cnido, opera realizzata dallo scultore Prassitele intorno al 330 a.C. e passata alla storia per essere la prima statua di nudo femminile a grandezza naturale (l’originale è andato perduto, ma ne sono state realizzate centinaia di versioni in marmo).

ENG

We must look at this revolution not so much as a mere stylistic turning point, but as a revaluation of the female gender in its iconographic representation, with all the implications related to the reactions that such an erotic representation would have entailed.

Not by chance, the history of art has been crossed, over the centuries, by forms of agalmatophilia, carnal passions for works of art, so intense as to lead to madness. The Venus of Knidos was the protagonist of a similar episode, as told by Pseudo-Lucian in his Amores and Philostratus in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana, without forgetting the story of Pygmalion.

Harnessing provocative nudity is a concept that will accompany the entire Medieval period, where women are martyrs, saints and virgins. With the Renaissance, the Christian heritage was abandoned in favor of a new concept of the body. Where everything was a reason for study, interest and cultural growth, the body is not hidden, but investigated. An image well known to the history of art is the Allegory of Spring, in which there is the exaltation of woman as the driving force of nature in her being a symbol of physical love and the personification of the arts.

ITA

A questa rivoluzione dobbiamo guardare non tanto come una mera svolta stilistica, bensì come una rivalutazione del genere femminile nella sua rappresentazione iconografica, con tutte le implicazioni relative alle reazioni che una rappresentazione così erotica avrebbe comportato.

Non a caso, la storia dell’arte è stata attraversata, nei secoli, da forme di agalmatofilia, passioni carnali per le opere d’arte, così intense da condurre alla follia. Proprio la Venere di Cnido è stata protagonista di un simile episodio, come raccontano lo Pseudo-Luciano nei suoi Amores e Filostrato nella sua Vita di Apollonio di Tiana, senza dimenticare la storia di Pigmalione.

Imbrigliare la provocante nudità è un concetto che accompagnerà tutto il periodo Medievale, dove la donna è martire, santa e Vergine. Con il Rinascimento, si abbandona il retaggio cristiano per approcciare ad una nuova concezione di corpo. Laddove tutto era motivo di studio, interesse e accrescimento culturale, il corpo non va nascosto, ma indagato. Un’immagine ben nota alla storia dell’arte è l’Allegoria della Primavera, in cui avviene l’esaltazione della donna quale forza motrice della natura nel suo essere simbolo di amore fisico e che personificazione delle arti.

ENG

To the few gifted with particular mastery in the arts, the possibility of giving free rein to their abilities, launching themselves into challenges of anatomy and sensuality.

Proud women were born, sometimes gentle and sinuous, others muscular and powerful, with masculine features. The body is harmony, perfection, it lends itself to be admired, certainly, but now we work on the detail: the gesture, the look, the unspoken.

What can we add to Raphael’s marvelous Madonnas?

ITA

Ai pochi dotati di particolare maestria nelle arti, la possibilità di dare libero sfoggio delle proprie capacità, lanciandosi in sfide a colpi di anatomia e sensualità.

Nascono donne procaci, a volte gentili e sinuose, altre muscolose e possenti, dalle fattezze maschili. Il corpo è armonia, perfezione, si presta ad essere ammirato, certamente, ma ora si lavora sul dettaglio: il gesto, lo sguardo, il non detto.

Cosa aggiungere delle meravigliose Madonne di Raffaello?

ENG

His women are welcoming mothers, whose expressions conceal all the love and pain of an already written destiny.

Tales of women different in the centuries, but always equal to themselves in their own historical moment. A space-time break occurred when an element of social diversification was introduced that touched not only men, but also women: it is the advent of the industrial revolution at the end of the eighteenth century. It is in this way that working-class women, dedicated to work in the fields (later also devoted to social revolts and factory work as a response to the terrible famines of the period) and upper middle-class women, dedicated to the quiet daily family life, Sunday walks and social events, coexist in the same era. The emancipation of women and self-determination is making its way, albeit at different rates in each European country.

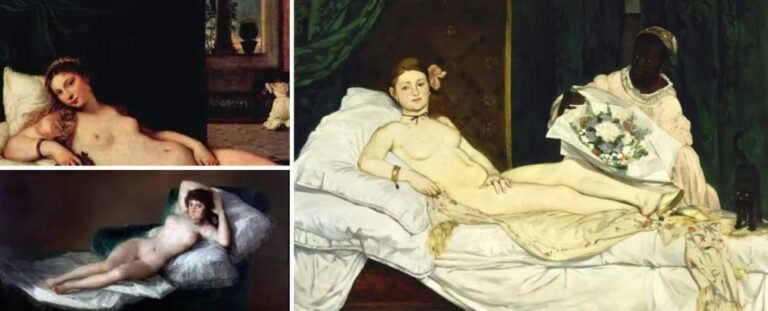

Even, with his “Olympia” Manet reveals that tradition started by Titian, passing through Goya with the “Maja Desnuda”, which tells the woman in an unequivocal profession.

ITA

Le sue donne sono madri accoglienti, che celano nell’espressione tutto l’amore e il dolore di un destino già scritto.

Racconti di donne diverse nei secoli, ma pur sempre uguali a se stesse nel proprio momento storico. Una rottura spazio-temporale è avvenuta laddove si è introdotto un elemento di diversificazione sociale che toccasse non solo gli uomini, ma anche le donne: è l’avvento della rivoluzione industriale sul finire del Settecento. È così che convivono nella stessa epoca donne operaie, dedite al lavoro nei campi (poi anche votate alle rivolte sociali e al lavoro in fabbrica anche come risposta alle terribili carestie del periodo) e di alta borghesia, dedite alla quieta quotidianità familiare, alle passeggiate domenicali e agli eventi mondani. Si fa strada l’emancipazione femminile e l’autodeterminazione di sé, seppur con ritmi diversi in ciascun paese europeo.

Addirittura, con la sua “Olympia” Manet si palesa quella tradizione iniziata da Tiziano, passando per Goya con la “Maja Desnuda“, che racconta la donna in una professione inequivocabile.

ENG

This greater social involvement results, in the Victorian era, in a cultured woman, a lover of the arts, such as literature, music and painting, but still harmless, like a precious cameo adorning the house and her man. A risk that Klimt caresses in his paintings, with female protagonists of a terrible and bloody eroticism.

ITA

Questo maggior coinvolgimento sociale si traduce, in epoca vittoriana, in una donna colta, amante delle arti, quali letteratura, musica e pittura, ma pur sempre innocua, come un cammeo prezioso che adorni la casa e il suo uomo. Un rischio che Klimt accarezza nei suoi dipinti, con protagoniste figure femminili di un erotismo terribile e cruento.

ENG

The female nude in the 20th century wears and shows its sensuality with a complete reversal of course compared to the scenario from which we started, when the only nude allowed in art was male.

Today, free from any prejudice, we no longer narrate a gender, relegated to a status or social role, but the harmony, fluidity and history that flows between the tortuous curves and folds of the skin.

Perfection is not in the shapes of the body, but in the balance between what appears and what one is deep inside. Is it really so essential to investigate the identity? Perhaps the secret to grasping the heart and intellect of a human being lies in not allowing oneself to be distracted by appearance.

ITA

Il nudo femminile nel Novecento indossa e mostra la propria sensualità con una completa inversione di rotta rispetto allo scenario da cui siamo partiti, quando l’unico nudo ammesso nell’arte era quello maschile.

Oggi, liberi da qualsiasi pregiudizio, raccontiamo non più un genere, relegato ad uno status o ruolo sociale, ma l’armonia, la fluidità e la storia che scorre tra le tortuose curve e le pieghe della pelle.

La perfezione non è nelle forme del corpo, ma nell’equilibrio tra ciò che appare e ciò che si è nel profondo. È davvero così indispensabile indagarne l’identità? Forse il segreto per cogliere il cuore e l’intelletto di un essere umano sta nel non lasciarsi distrarre dall’aspetto.