05 Apr Learning to listen to yourself in the silence of nature

by Serena Nardoni

ENG

Breezy is curating an exhibition that will be held in Rome, at the Ex Cartiera on the prestigious Via Appia Antica, on April 22nd – 30th, to investigate the complex relationship between human beings and technology through the eyes of our time. To introduce the event and all the artists who will take part in it, we would share with you the process of research and study behind the creation of a curatorial concept titled: I(m)perfection: the laws of technology that dominate order and chaos. We will do this with short essays that will look at technology in its relationship with the concept of beauty, in its evolution through the centuries. We will talk about art and philosophy, order and chaos, mathematical weighting and improvisation. The question with which we want to introduce you to the reading is: Where does the purest and most authentic concept of beauty reside? In the proportion and balance of forms or, rather, in the undisciplined chaos?

ITA

Breezy sta curando una mostra che si terrà a Roma, presso l’ex Cartiera sulla prestigiosa Via Appia Antica, il 22 – 30 aprile, per indagare il complesso rapporto tra essere umano e tecnologia con gli occhi del nostro tempo. Per accompagnare l’evento ed introdurre tutti gli artisti che vi prenderanno parte, abbiamo pensato di condividere con voi il processo di ricerca e studio che c’è dietro l’ideazione di un concept curatoriale dal titolo: I(m)perfection:le leggi della tecnica che dominano l’ordine e il caos. Lo faremo con dei brevi saggi che guarderanno alla tecnologia nel suo rapporto con il concetto di bellezza, nella sua evoluzione attraverso i secoli. Parleremo di arte e filosofia, di ordine e caos, di ponderazione matematica ed improvvisazione. L’interrogativo con cui vogliamo introdurvi alla lettura è: Dove risiede il concetto più puro e autentico di bellezza? Nella proporzione ed equilibrio delle forme o, piuttosto, nel caos indisciplinato?

Learning to listen to yourself in the silence of nature

ENG

Saying that something is beautiful is a judgment; the thing is not beautiful in itself, but in the judgment that defines it as such.

– Giulio Carlo Argan, L’arte moderna 1770/1970

Until now we have tried to pursue order, to search for harmony and beauty, to anchor what we know to some law of men… Today we take all this and try to look beyond.

Beyond the schemes are hidden, perhaps, the most sincere and purest essence of beauty, as well as our true essence. The impulse of the human being has always been directed towards the achievement of new goals, self-knowledge, tangible reality or not, but there are phenomena that escape our control and predetermination. Can this sense of powerlessness affect our common sense of balance and harmony? This question has moved the minds of writers, philosophers and artists of a particular era, the one between the mid-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The vehicle of this mental revolution is the Enlightenment, which suggests an idea of perfection that passes through a new key to understanding nature, no longer immutable form and always equal to itself, which can only be copied. Modern man is not subject to the laws of nature, but can choose to impose his own imprint and transform it, with an unlimited range of possibilities. On the basis of the different attitude of the human being before nature and his propensity to embrace his own active role, Kant bases his critique of judgment, distinguishing a “picturesque beauty” and a “sublime beauty”. Two thoughts that arise in the wake of Romanticism, drawing from it the feeling, the internalization of emotions and returning a subjective and personal vision, radiant or tormented that is of reality. The phenomenon, of course, is not accidental: with the advent of industrial technology, craftsmanship goes into crisis and the artist has the need to reinvent himself. Excluded from the industrial system, artists became independent bourgeois intellectuals and profoundly different currents of thought flourished.

The spirit of the picturesque is fully expressed in the landscape painting of the eighteenth century, as an expressive form of the intimate feeling of the artist who escapes the rigid laws of perspective and design. What the artist seeks is variety, the unpredictable: there is no universal concept of beauty, what is pursued is to translate the tangible sensation into feeling.

Nature, in its infinite manifestations, is a difficult concept to embrace with the mind. This suggests in another part of the world of art and literature a feeling of powerlessness. Man is an invisible point in the universe: in front of stormy seas and icy moors, we can only feel tiny, at the mercy of phenomena that we cannot deceive ourselves into controlling.

The positions of the picturesque and the sublime are translated into two different types of gardens, drawing the attention of art historians to a theme that has hardly aroused the same interest in other eras. In the first half of the eighteenth century was born the so-called “English garden” which, looking at the oriental model, is presented as an apparently uncultivated and spontaneous garden. On the contrary, the Italian garden is characterized by an orderly organization of space and vegetation, with flower beds and hedges designed to convey the view towards a perspective reading and a privileged point of observation that amplifies the space or provides spectacular water features (famous are the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, near Rome and the Boboli Gardens in Florence).

Such contrasting conceptual visions could only result in equally different expressive languages. So, if the picturesque is expressed through warm and bright tones, with vibrant touches that emphasize the particular, the dissonant detail in a quiet rural village, the sublime suggests a catastrophic vision of the future, with dark colors, pale, hard drawing and bodies that struggle but remain imprisoned in geometric patterns from which it is impossible to escape.

Imparare ad ascoltarsi nel silenzio della natura

ITA

Dire che una cosa è bella è un giudizio; la cosa non è bella in sé, ma nel giudizio che la definisce tale

– Giulio Carlo Argan, L’arte moderna 1770/1970

Ebbene, abbiamo fino a qui cercato di perseguire l’ordine, ricercare armonia e bellezza, di ancorare ciò che conosciamo ad una qualche legge degli uomini… Oggi prendiamo tutto questo e cerchiamo di guardare oltre.

Oltre gli schemi si celano, forse, l’essenza più sincera e pura della bellezza, nonchè la nostra vera essenza. Lo slancio dell’essere umano è sempre stato volto verso il raggiungimento di nuovi obiettivi, della conoscenza di sé, della realtà tangibile o meno, ma esistono fenomeni che sfuggono al nostro controllo e alla predeterminazione. Può questo senso di impotenza intaccare il nostro comune senso di equilibrio e armonia? Questo interrogativo ha smosso gli animi dei letterati, filosofi e artisti di un’epoca in particolare, quella a cavallo tra la metà del Settecento e l’Ottocento.

Il veicolo di questa rivoluzione mentale è l’Illuminismo, che suggerisce un’idea di perfezione che passa per una nuova chiave di lettura della natura, non più forma immutabile e sempre uguale a se stessa, che si può solo copiare. L’uomo moderno non sottostà alle leggi della natura, ma può scegliere di imporvi la propria impronta e trasformarla, con un ventaglio di possibilità illimitato. In base al diverso atteggiamento dell’essere umano dinanzi alla natura e alla sua propensione ad abbracciare il proprio ruolo attivo, Kant fonda la sua critica del giudizio, distinguendo un “bello pittoresco” e un “bello sublime”. Due pensieri che nascono nel solco del Romanticismo, traendone il sentimento, l’interiorizzazione delle emozioni e restituendo una visione soggettiva e personale, radiosa o tormentata che sia della realtà. Il fenomeno, ovviamente, non è casuale: con l’avvento della tecnologia industriale, l’artigianato entra in crisi e l’artista ha la necessità di reinventarsi. Esclusi dal sistema industriale, gli artisti diventano intellettuali borghesi indipendenti e fioriscono correnti di pensiero profondamente diverse.

Lo spirito del pittoresco si esprime pienamente nella pittura paesaggistica del Settecento, quale forma espressiva dell’intimo sentimento dell’artista che si sottrae alle rigide leggi della prospettiva e del disegno. Ciò che l’artista cerca è la varietà, l’imprevedibile: non esiste un concetto universale del bello, ciò che si persegue è tradurre la sensazione tangibile in sentimento.

La natura, nelle sue infinite manifestazioni, è un concetto difficile da abbracciare con la mente. Ciò suggerisce in un’altra parte del mondo dell’arte e della letteratura un sentimento di impotenza. L’uomo è un punto invisibile nell’universo: dinanzi a mari in tempesta e lande ghiacciate, non possiamo che sentirci minuscoli, in balia di fenomeni che non possiamo illuderci di controllare.

Le posizioni del pittoresco e del sublime si traducono in due diverse tipologie di giardino, attirando le attenzioni degli storici dell’arte su un tema che difficilmente ha destato lo stesso interesse in altre epoche. Nella prima metà del Settecento nasce il cosiddetto “giardino all’inglese” che, guardando al modello orientale, si presenta come un giardino apparentemente incolto e spontaneo. Al contrario, il giardino all’italiana si caratterizza per un’organizzazione ordinata degli spazi e della vegetazione, con aiuole e siepi studiate per convogliare lo sguardo verso una lettura prospettica e un punto di osservazione privilegiato che amplifica lo spazio o prevede giochi d’acqua spettacolari (celebri sono la villa d’Este a Tivoli, nei pressi di Roma e il Giardino dei Boboli a Firenze).

Da visioni concettuali così contrapposte, non potevano che derivare linguaggi espressivi ugualmente diversi. Ecco che se il pittoresco si esprime attraverso tonalità calde e luminose, con tocchi vibranti che danno risalto al particolare, al dettaglio dissonante in un quieto villaggio contadino, il sublime suggerisce una visione catastrofica del futuro, con colori foschi, pallidi, disegno duro e corpi che si dimenano ma restano imprigionati in schemi geometrici da cui è impossibile fuggire.

ENG

As in Friedrich’s painting, a manifesto of the sublime, we are there, standing on a rock, helplessly observing the spectacle at our feet. A view that is certainly fascinating, extending as far as the eye can see, but which leaves open the doubt of what lies beyond, what escapes comprehension? Thoughts and feelings that the traveler faces in his own interiority. He, who has set out on this journey to contemplate the terrible spectacle of nature, reflects on the choices he has made, the opportunities lost, the expectations and fears that are to come.

ITA

Come nel dipinto di Friedrich, manifesto del sublime, noi siamo lì, in piedi su una roccia, ad osservare impotenti lo spettacolo ai nostri piedi. Una vista certamente affascinante, che si estende a perdita d’occhio, ma che lascia aperto il dubbio su cosa ci sia oltre, cosa sfugge alla comprensione? Pensieri e sentimenti che il viandante affronta nella propria interiorità. Lui, che si è incamminato in questo viaggio per contemplare lo spettacolo terribile della natura, riflettere sulle scelte fatte, le opportunità perdute, le aspettative e le paure che verranno.

ENG

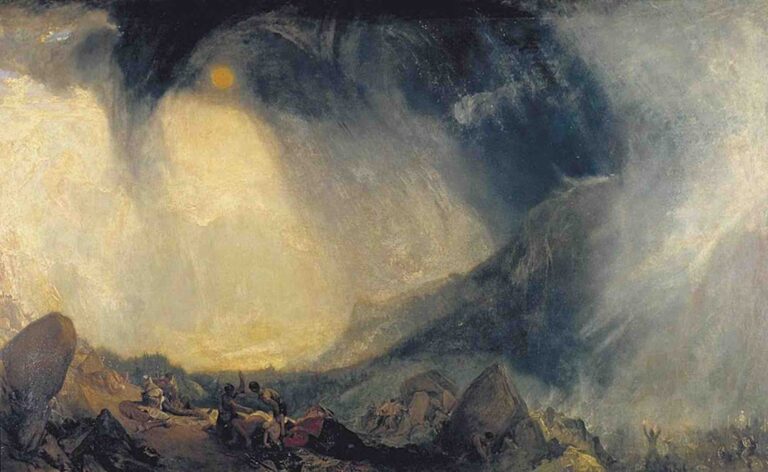

Among the greatest interpreters of the spirit of the sublime, Turner is known as the painter of light.

That light which has no boundaries, and which, according to Goethe’s theory, is a light which “shapes reality”, which frees it from rules. It is not by chance that Turner dedicated what we can consider as the manifesto of his painting to the German writer (Light and Color – Goethe’s Theory, 1843). If we did not read the title of the work, it would be difficult to trace the theme represented. The historical episode, in fact, is only the expedient to be able to project tension and pain in the sky, full of a snowstorm.

Next to the impetuous flow of nature and the impotence of the human being, there is the flourishing of memories of happy moments spent in the authentic life of the countryside. An emotional bond is created with nature, which is welcoming, delighting heart and spirit.

In John Constable’s painting, The Hay Wagon, a common scene of bucolic life in the Sufflok countryside is immortalized: a hay wagon stops next to a stream in which a modest house is mirrored, flanked by shady trees. In the background, vast cultivated fields are touched by the light that breaks through the clouds. Everything is calm and on a human scale.

Unlike Turner’s skies, Constable’s are serene and convey positive, personal emotions and nothing more. If in Turner, in fact, it is not uncommon to find representations of mythological, biblical or historical scenes, whose emotions are reflected in the atmospheric phenomena, in Constable nature does not allude to anything more than itself.

Under his skies, Constable depicts only what he has known and frequented: the Suffolk region, the hills of Hampstead and the surroundings of Salisbury.

ITA

Tra i maggiori interpreti dello spirito del sublime, Turner è conosciuto come il pittore della luce.

Quella luce che non ha confini, e che secondo la Teoria di Goethe, è una luce che “plasma la realtà”, che la svincola dalle regole. Non è un caso che Turner abbia dedicato quello che possiamo considerare come il manifesto della sua pittura allo scrittore tedesco (Light and Colour – Goethe’s Theory, 1843). Se non leggessimo il titolo dell’opera, difficilmente potremmo risalire al tema rappresentato. L’episodio storico, infatti, è solo l’espediente per poter proiettare tensioni e dolore nel cielo, carico di una tempesta di neve.

Accanto all’impetuoso fluire della natura e all’impotenza dell’essere umano, c’è il fiorire dei ricordi di momenti felici trascorsi nella vita autentica della campagna. Si crea un legame affettivo con la natura, che è accogliente, delizia cuore e spirito.

Nel dipinto di John Constable, Il carro di fieno, si immortala una scena comune della vita bucolica nella campagna di Sufflok: un carro di fieno sosta accanto ad un corso d’acqua nel quale si specchia una modesta abitazione, fiancheggiata da alberi ombrosi. Sullo sfondo, vasti campi coltivati toccati dalla luce che irrompe dalle nubi. Tutto è calmo e a misura d’uomo.

A differenza dei cieli di Turner, quelli di Constable sono sereni e trasmettono emozioni positive, personali e nulla di più. Se in Turner, infatti, non è raro trovare rappresentazioni di scene mitologiche, bibliche o storiche, le cui emozioni si riverberano nei fenomeni atmosferici, in Constable la natura non allude a nulla più di se stessa.

Sotto i suoi cieli, Constable rappresenta solo ciò che ha conosciuto e frequentato: la regione del Suffolk, le colline di Hampstead e i dintorni di Salisbury.

ENG

So that sense of unpredictability and changeability of reality does not necessarily frighten, but also moves. Freed from the rigid arguments of those who have long striven to give an explanation to the most mysterious thing that exists, that is life, opens that chapter of art history that will chase dizzily the affirmation of the author’s personality. It is no coincidence that at the end of the eighteenth century artists began to give a personal title to their works that are no longer mere representations of what is or has been, but poetic verses that tell another dimension: that of the human soul.

ITA

Quindi quel senso di imprevedibilità e di mutevolezza della realtà non per forza spaventa, ma anche commuove. Liberati dalle rigide argomentazioni di chi si è a lungo sforzato di dare una spiegazione a ciò che di più misterioso esiste, ossia la vita, si apre quel capitolo della storia dell’arte che inseguirà vertiginosamente l’affermazione della personalità dell’autore. Non è un caso che proprio alla fine del Settecento gli artisti iniziano a dare un titolo personale alle proprie opere che non sono più mere rappresentazioni di ciò che è oppure è stato, ma versi poetici che raccontano un’altra dimensione: quella dell’animo umano.